REFORMED PASTS: ANNET COUWENBERG AT THE BMA

Kerr Houston on From Digital to Damask at the Baltimore Museum of Art

Rather like the Baroque lace collars that serve as its partial inspiration, Annet Couwenberg’s From Digital to Damask is modest in scale, but quickly reveals a beguiling underlying complexity.

Featuring ten recent works, the two-room show (on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art through next February) is at once a study in formal structures, an exercise in applied technology, and a meditation on personal and national art histories. It’s governed, in other words, by an investigative spirit that yields new ways of thinking about relatively familiar tropes.

The exhibition is the outcome of a galvanizing collaboration. In 2014, Couwenberg, a longtime professor in MICA’s Fiber department, was awarded a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. Working with Lynne Parenti, an expert in vertebrate anatomy at the National Museum of National History, Couwenberg used several advanced imaging technologies to study the skeletal structures and skin geometries of various species of fish. She was thus a modern descendant, you might say, of Samuel Scudder, who once spent days studying a single fish under the guidance of the biologist Louis Agassiz, slowly seeing more deeply into the shape and construction of the animal.

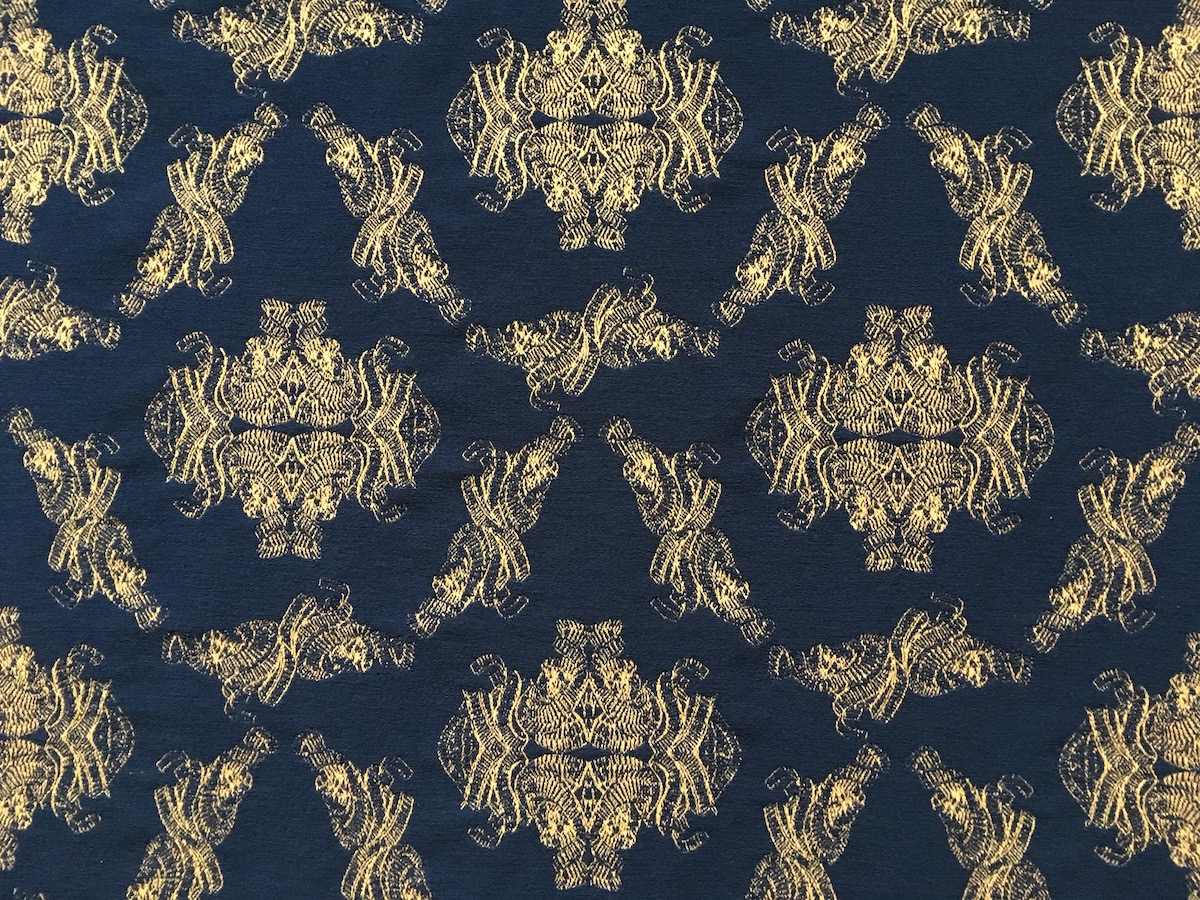

Intrigued by what she saw, Couwenberg executed a series of intricate line drawings, and then began to produce more substantial works that drew on her experience as a fiber artist and that also alluded to the rich artistic traditions of her native Holland. At a textile laboratory, she designed a series of damask panels whose primary motifs are derived from piscine details, but whose marginal designs recall the lacework of Zeeland, where Couwenberg spent time as a child. Her use of damask, moreover, was apparently inspired by the black painted fabric in a Frans Hals portrait owned by the BMA: a fabric that she then rendered in a deep blue reminiscent of the traditional ceramics of Delft. The four exhibited textiles, then, are dense mash-ups of biological, art historical, and autobiographical source materials.

Six mixed-medium sculptures constitute the rest of the work on display, and also embody a central interest in synthesis and relational thinking. Stimulated by the elegant organic relationships between surface and substructure that she had observed at the museum, Couwenberg used digital laser cutters to produce hundreds of modular polyurethane units and to perforate lengths of stiff cotton buckram. Folding the cloth, and mooring it on the plastic supports, she then produced a series of spiraling forms that recall lace collars while also expressing a spirit very much their own. At once calligraphic and geometric, volumetric and fragile, they are the product of precise technology and traditional handiwork: intricate explorations, you might say, of the various conflicting senses of the terms digital and manufacture.

The idea of using contemporary digital technologies to produce forms associated with the traditional fiber arts is, it’s worth noting, not a unique one. Indeed, examples of such a tendency have proliferated over the past decade. From Lizz Aston’s lace mirrors to on-screen re-workings of Malay telepuk motifs, and from the Digital Lace project to the book Crafting Textiles in the Digital Age, there is a broad, demonstrable interest in the possibilities inherent in emergent modes of production.

Still, Couwenberg’s work arguably stands out among that of her peers due to the ambitious and nuanced quality of the thought processes behind it – and her high standards of production. For these are ravishing objects, their obvious complexity tempered by a crisp precision and a balance between elaborate patterns and bold governing forms. And while some artists have exploited new technologies rather uncritically, trying out new technologies simply because they can, Couwenberg employs them pointedly and productively, seeking out areas of contact and of tension between the traditional and the contemporary.

This is thus a show centrally interested in relationality: in the juxtaposition of technologies, in the migration of ideas across borders and in supra-historical analogies. Couwenberg delights in associating disparate forms (fish skeleton, lace) from diverse moments (Baroque, post-digital). In these senses, the show seems to want to dissolve conventional boundaries, and recalls Bob Hodge’s characterization of transdisciplinarity as “mingling discipline with discipline in a promiscuous mix.”

Above all, though, Couwenberg’s works reminded me of James Elkins’ Visual Culture, a lively study that is similarly open to a wide variety of forms and technologies. Like Couwenberg, Elkins is fundamentally intrigued by the history of artistic motifs: by training, he’s a Renaissance art historian. But his book also embodies an active interest in scientific imagery, as it features a photograph of a dinoflagellate, a computer image of an eye, and frames from a movie of rhodium atoms. Elkins isn’t necessarily out to dislodge traditional modes of inquiry; as he puts it, “I am not proposing a new technophilia, simply a new inclusiveness. Images cross boundaries that humanists do not.” And so too with Couwenberg, who has created an arena in which novel possibilities of seeing, and relating, emerge.

One final point. Too often, I think, we passively assume that digital technologies are simply points of departure, facilitating new possibilities. Thus, for example, the title of this show, which positions the fabric on display as the outcome of digital work, and thus too the claim, in a wall text, that “Couwenberg’s textiles call attention to the ways in which digital technology can contribute to artistic design.” That’s not untrue, but it also seems to me to be only part of the story. For one can fairly argue the converse, as well, by pointing out that certain fiber arts actually embodied, long ago, the sort of binary logic that only later came to underlie all digital technologies.

Lacework, in other words, can be said to have anticipated the structure of digital languages. Or, to put it a bit more pointedly: just as one can move from digital to damask, one can also trace a trajectory from damask to digital.

That’s a point that was once made by Sir Ernst Gombrich, in his classic text Art and Illusion. “There are many media of art in which such an ‘on’ or ‘off’ principle is applied,” he noted. “Let us think of certain types of drawn work or lace in which the netting is filled in or left empty of pattern but still gives perfect images of men and beasts… All that counts is the relationship between the two signals.” Lacework, in other words, can be said to have anticipated the structure of digital languages. Or, to put it a bit more pointedly: just as one can move from digital to damask, one can also trace a trajectory from damask to digital.

Evolving technologies, then, are certainly exciting. But they are the product, of course, of lengthy histories, of earlier precedents and extended experimentation. And, even as they change the ways in which we perceive, relate to, and even manufacture the world around us, they don’t entirely supplant the considerable rewards of simply looking closely. Indeed, that was one of the lessons that Samuel Scudder learned more than a century ago, as he stared at the fish before him, not yet allowed to use scalpel or microscope. And, happily, it’s a truth also implicit in the work of Couwenberg, who is admirably willing to experiment with new tools, but who also recognizes the fundamental allure of the extant, the familiar, and the received.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.

Annet Couwenberg will speak about her work in the English Sporting Gallery at the Baltimore Museum of Art on September 10, at 3 p.m.

Annet Couwenberg: From Digital to Damask will be on display at the Baltimore Museum of Art through February 18, 2018.

Images courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art